Environmental managers I work with have expressed concern about the increased scope of the draft ISO 14001:2015 standard, in so much as it extends to processes and departments such as procurement and design that they have little or no influence over, and especially the need for greater involvement of top management with whom they already struggle to engage on the basics of pollution prevention and compliance.

I sympathise with this view to the extent that if you (as an environmental or sustainability manager) go to your top management with the approach: “ISO now says you have to do x, y, and z in order to maintain certification”, it is unlikely to go down well — you will be banging the same old drum, only louder.

Part of the reason for this anxiety is that environmental management is seen by some business leaders to be mainly about mitigating risk and, therefore, an operational on-cost. In the same organisations strategic decisions are made at a high level to restructure the business, develop new products and services, and move into new markets, without any consideration of the environmental or sustainability implications. Leaders then get frustrated with environmental managers for raising constraints associated with capacity or regulation.

However there is another way of thinking about environmental management — it is ‘what you do’ as an organisation, as well as ‘how you do it’. Not only is this way of thinking likely to do more favours for the environment (the life cycle impacts of your product or service may be ten times greater than your operational impacts), it is much more likely to engage top management in environmental and sustainability thinking — because what you do has implications for business strategy, customers and sales. Your portfolio of products and services is also fertile ground in which to grow environmental opportunities for your organisation.

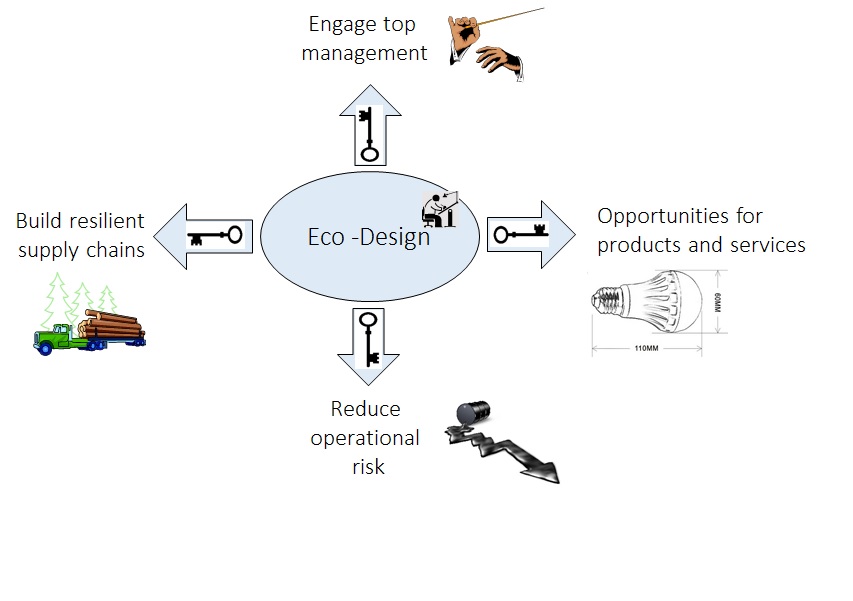

The ‘ISO 14001:2015 Road Test’ group I facilitated last year concluded that four of the key areas in ISO 14001:2015 that will require the greatest amount of change for organisations are: an increased focus on leadership and strategy; determining and addressing risks and opportunities; environmental purchasing; and environmental design and development of products and services. I believe that it is the last of these – the design of your product or service from an environmental, and potentially sustainability, point of view (that I will refer to as eco-design) – is the key to unlocking the benefits of ISO 14001:2015. In this article, I will explain why, and how to make a start on this journey.

Whether your organisation makes products, buildings or infrastructure, or delivers a service — design is king or queen. It defines who you are and what sets you apart from your competitors. Design drives every other aspect of the business from the raw materials that you purchase, operations and risk on the shop floor, to your marketing and sales strategies.

My thinking about the centrality of eco-design for environmental management is illustrated in the following diagram:

Reduce operational risks

The design of your product or service has critical implications for operational risks; I shall illustrate this with an example from my early working life in the electricity distribution industry.

As an environmental manager I was involved with a range of issues such as oil leaks from underground cables, toxic chemicals (PCBs) used in transformers, monitoring and reducing the impact of a potent greenhouse gas (SF6) used in switchgear, and dealing with groups who opposed overhead lines due to their visual and wildlife impact. Management of these issues took a lot of time, and also money. Millions were spent on retrofitting transformers with secondary containment, installing large spill kits, and remediating contaminated land.

Some of these issues were always known to have an environmental impact, such as oil leaks; others had only become apparent more recently, such as the impact of SF6. Nevertheless, I learnt that network designers made key decisions at the planning stage such as whether the lines will be overhead or underground, the route, the capacity and type of transformers used, the switchgear technology to be employed (vacuum, air, gas), and the methods used for protection — all of which had major implications for the lifetime environmental and safety implications of the network.

For this reason I was at pains to include the network designers in the environmental management process. I knew that if eco-design principles were employed, such as removing toxic materials and the consideration of lifetime management costs, then problems could be dealt with up front, eliminating or reducing the pollution risk, associated regulatory risks, and clean-up costs.

As well as reducing pollution risk, eco-design principles can substantially decrease the lifetime energy costs of a product or project. This is as true when specifying low-loss, or higher-loss transformers (that may be operating for the next 40 years), as it is when constructing a building, or designing a washing machine. The challenge here is to effectively communicate to the organisation, or customer, that by paying a little extra up front, they will enjoy many years of savings. In my experience organisations also need to join-up thinking between capital and revenue budgets.

To give an example from a different industry sector: in ‘Business Lessons from a Radical Industrialist’ by the late Ray Anderson (founder of the carpet company Interface, and frequently hailed exemplar of sustainability) he describes establishing a Toxic Chemicals Elimination team to eliminate ecologically damaging chemicals from all Interface facilities. The team had a hard time obtaining all the information they needed from their supply chain, but eventually developed and implemented a screening protocol. Not only did they screen out toxics such as lead and mercury, they reportedly saved money in the process, and reduced the number of discharges to air and water from their factories. While some of these improvements were mainly associated with the manufacturing process, they termed the initiative ‘benign by design’ — changing the substances used in their carpet tiles was a designer led process, but part of the benefits were enjoyed by manufacturing.

Build resilient supply chains

Companies are increasingly concerned about the resilience of their supply chains. The supermarket chain ASDA, for example, recently reported that 95% of their fresh produce range is at risk from climate change. As a result, they are implementing a framework to adapt to these risks that will involve looking into the detail of their most vulnerable products.

Informed purchasing departments can do a lot when it comes to green purchasing and building resilient supply chains, but there is another side to sustainable purchasing policy that goes to the heart of what the organisation does.

Last year I attended an informative sustainable procurement conference in Birmingham. There were a range of speakers who worked in sustainable procurement, from the BBC to a large ceramic tile manufacturer. These organisations had complex global supply chains, employing thousands of individuals, across several continents. There were discussions about the best way to engage with supply chains to ensure that social, economic, and environmental criteria were embedded. Techniques employed ranged from traditional questionnaires and supply-chain audits, to more innovative engagement with small groups of suppliers, using storytelling and role-play to effect change.

However, as the event progressed I was struck by the revelation that many of these purchasing managers are in a similar position to operational environmental managers. They are given a shopping list of what to buy and have to get on with it, doing their best to minimise risk. Towards the end of the day I plucked up the courage to ask a question to the panel: “Do you have the opportunity to influence what you are purchasing, or just who from?” The consensus answer was: in the main they can’t influence what they are buying because they have no role in the design of the product or service.

It stands to reason that in order to make a paradigm shift in the environmental and sustainability impact of your supply chain, some organisations may need to think about design of their product or service, with the aim of eliminating problematic product lines and materials, rather than shopping around for the least-worst procurement option.

One organisation I have worked with on environmental management is a metal fabricator – they have ISO 14001 and good environmental controls. One of their largest customers recently insisted that they switch from more environmentally friendly powder to coat their products to solvent-based paint. Although this change would mean greater environmental impact, and regulatory burden, they had little choice other than to lose the contract. A design specification made by that customer embedded greater environmental impacts in their supply chain. The purchasing department of that customer could send out a supplier questionnaire, and do monthly supplier audits – but it would never change the fundamentals of their solvent specification. The lesson is clear – the principle ‘benign by design’ also has implications for your supply chain, as well as direct operations.

A complementary way to reduce the environmental impact of your supply chain, and also increase its resilience, is to move from a ‘take-make-break’ business model, to a cradle to cradle, or circular economy model. There is a misconception that the ‘circular economy’ is primarily about operations – diverting waste from landfill at the back door of the factory. But in order to create products that can be readily disassembled so that their valuable, uncontaminated materials become the feedstock for the next products, they often need to be redesigned from the ground upwards.

Jaguar Land Rover, who also presented at the supply-chain seminar I attended, explained that learning from life cycle assessment studies of their vehicles has informed their decision to switch from heavier steel, to lighter aluminium, for car chassis. They reported that although the initial environmental impact of the aluminium is greater than steel, benefits are gained during the use phase for both the customer and environment, and the company has an ambitious strategy to work with myriad stakeholders to take back and reuse aluminium from their old vehicles to make new ones. Because recycled aluminium only has 5-10% of the environmental impact of virgin aluminium, they can potentially reuse it an unlimited number of times, reducing the environmental impact of their supply chain, whilst simultaneously creating a new source of raw materials for their vehicles – increasing business resilience.

New opportunities for product and services

Sometimes there is a perception that environmental friendly products only appeal to the niche market, and one has to suffer to use them — this is not entirely without basis. I remember buying ten, expensive, first-generation LED lights for our kitchen — they were about as effective as a candle and emitted an eerie blue glow. Needless to say, they are still sitting unloved in a box under the stairs.

However, it doesn’t have to be like this, and increasingly consumers are differentiating on issues that are complementary to the green agenda such as efficiency, and free of toxic materials, but they don’t necessarily think of themselves as green consumers. Who wants to be lumbered with toxic, heavy, inefficient products that are expensive to run, and difficult to dispose of?

Today there are a plethora of decent products on the market that tick green boxes without specifically being marketed as such: washing powders that clean at lower temperatures; lighter, more efficient vehicles with lower emissions; low-solvent paint; houses that cost almost nothing to run; and websites for sharing everything from your spare bedroom, to a drill. One of my favourite possessions that falls into this category is my portable radio — vital for an itinerant Radio 4 addict. My old portable radios often broke, and the batteries were constantly running out. I switched to a ‘Roberts’ radio that allows for the internal recharging of batteries when plugged in. It also has an unusually robust aerial, and detachable colour rims that can be switched to suit your taste or decor. I have no idea whether Roberts specifically designed this radio with sustainability in mind (it is not overtly marketed as such), but for me it ticks three eco-design boxes: it produces less waste during use, has increased durability, and has modular elements. Good design is good design – there should be no surprise when this is also the friend of sustainability.

By incorporating eco-design principles into your product or service, you shouldn’t need to compromise on performance or sustainability. Gareth Kane has convincingly made the case that greener products must compete on price, performance, and the planet. And in his book, Green Jujitsu, he explains that it is not necessary to turn members of staff into eco-warriors in order to get their input into sustainability objectives but rather appeal to each individual’s strengths and creativity. If those objectives are right objectives, they should be good for business, and stand up on their own merits.

In their seminal book ‘Cradle to cradle’, Braungart and McDonough argue that designers should aim for eco-effectiveness above eco-efficiency. The difference between the two is explained using the example of a building: an eco-efficient building is worthy but also uninspiring, it is air-tight, with humming air conditioners, non-opening windows, and tinted glass, designed to house machines, not humans; an eco-effective building, on the other hand, employs biophilic design principles of space, light, nature and ventilation – delighting users and reducing employee sickness. Both can be energy efficient, but the latter enhances the lives of the people who work there. They sum up the umbilical link between design and sustainability: “Our concept of eco-effectiveness means working on the right things – on the right products and services and system – instead of making the wrong things less bad.”

This principle can apply to products, buildings, and even cities. In his recent book ‘Happy City’, Montgomery gives example after example that residents of greener, relatively dense cities, designed for people rather than cars, enjoy happier and healthier lives. Montgomery cites studies that found people who live next to green spaces in cities not only knew more of their neighbours and had stronger feelings of belonging, but also experienced lower levels of property and violent crime. While greenery is good, the American dream of living in a detached home on a leafy cul-de-sac backfires, because of the negative effects of long commutes on health, social cohesion, and one’s bank balance. Low-density sprawl, devoid of shops and natural meeting places, has a particularly pernicious effect on the young and old who cannot drive. Therefore planning and zoning policies, dictated by city planners, can have a substantial positive or negative effect on the health and wellbeing of residents, and perhaps not surprisingly the same policies that are good for people also reduce the environmental impact of the city.

So by employing eco-design principles designers can sometimes make products and services more efficient, effective, and delightful. There is no simple formula to achieving this, but some organisations are travelling in this direction – is your organisation amongst them?

A note about services

Many organisations are one or two stages in a long supply chain and their direct environmental impacts only represent a small share of the total environmental impact of the product. With regards to a service the same logic applies; by considering the design of services you can maximise your positive influence. What is taught in a school will potentially have a far greater impact on the lifetime environmental impact of a child compared with the environmental impact of the building – however working on the two together could have synergistic benefits. The service-related environmental impact of a planning department in a council (what types of buildings and infrastructure go where) is of paramount importance compared to how much paper they use in the office. Again, the lion’s share of the environmental impact of a travel agency is about the service they provide: poor tourism practices have devastated the environment in some areas (such as Cancun in Mexico), while good practices also exist that tread lightly and are restorative.

Sometimes switching your business model from a product-based approach, to a service, can reduce your environmental impact. For example by leasing products, rather than owning them, customers are ensured that the products are maintained in top condition, and they have ready access to the latest technology. You may also be in an industry sector where a physical product is being replaced by an electronic one, such as the switch from DVDs to video streaming. This is known as dematerialisation and may also have lower overall environmental impacts.

Services don’t just happen, they are planned (or designed), and way you design them has implications for the environment.

Engaging top management

At the beginning of this article I set out a potential problem raised by environmental managers, that the draft ISO 14001:2015 standard has new requirements that are not traditionally part of your remit, and it simultaneously requires greater engagement with top management — with whom you are already struggling to engage on the basics.

However, I have argued that you can use the new focus on the design of your products and services as the key to unlocking other new requirements: building more sustainable and resilient supply chains, and identifying opportunities for your product or service, whilst underpinning traditional pollution prevention and compliance requirements — from the point of view of top management, what is there not to like? It is a new message that environmental management can add value to your organisation, as well as reducing risk — ‘from compliance to opportunity’.

I put this to the test on a recent visit to an architect’s practice for whom I provide an internal audit service. Talking to the Directors about reducing office waste and energy consumption was moderately interesting, but the conversation came alive when it turned to the subject of embedding eco-design principles (such as passive house, fabric-first, and biophilia) into their architectural process. This is not surprising because architects are normally passionate about their profession, and if eco-design can be shown to help create better buildings and happier customers then it is a win-win.

How to do it

I have set out reasons why eco-design should be central to any environmental management system but how to do it?

Some organisations are already leading the field in this area and have tools that allow them to model the life-cycle implications of design changes on-the-fly. They can ask questions like: “What happens to the carbon or water footprint of our product if we reduce the packaging weight by 5%, or change from one type of material to another?”. However a full life cycle assessment may not be the most appropriate approach for all, and the draft version of ISO 14001:2015 specifically states that a full LCA is not required.

A simplified qualitative approach may be appropriate by asking a series of questions about your product or service associated with each stage of its life cycle. The answers to these questions could then be used to develop an action plan to reduce your environmental impacts, whilst simultaneously adding value to your organisation. No doubt it would be best to use a multidisciplinary team approach and you may wish to target them with a single product or service in the first instance. Ultimately consideration of eco-design principles should be embedded into your design process so that it becomes business as usual; the earlier that these principles are first considered the better the outcome for the product or service and environment. Initial considerations can be revisited and refined as the design and development process progresses. Ideally the outcome of changes will be measureable so that you can demonstrate environmental improvement, and justify any green-claims made.

Raw materials:

- Do our raw material / ingredient / subcontract specification embed environmentally damaging practices into our supply chain? If so can we change the specification?

- Are we maximising the recycled content in our raw materials?

- Can we incorporate reused / remanufactured / upcycled elements into our products?

- Can toxic materials be eliminated or reduced from our products and services?

- Can embodied carbon and water be reduced from our products and services?

- Does our product have any unnecessary components that can be eliminated? (Take it apart, have a look, challenge every component.)

- Can our product be made lighter? (Thus reducing the raw materials input, transport, and disposal costs.)

- Can the product be designed so that biological and technical materials (nutrients) are not mixed together (either in raw materials, or manufacture) in ways that they cannot subsequently be separated?

- Is packaging kept to a minimum, and excludes toxic materials?

Use:

- What environmental issues are our customers most concerned about with our project or service?

- Would it be more beneficial for the customer and environment if we leased our product(s) rather than selling them?

- Could we facilitate the sharing of our product / service rather than everyone owning one each? (A principle known as Factor Four – doubling wealth by halving resource use.)

- Can our product or service be redesigned so that it produces less waste when in use?

- Can our product or service be redesigned so that is uses less energy and water?

- Can our product or service be redesigned so that it is less noisy, or reduces any other environmental impact during use?

- Can our product or service be redesigned so that it is restorative – it gives back more to nature than it takes?

- Can our product or service be designed so that it lasts longer?

(A key definition of LCA is functional unit. A product that lasts four times as long, but has double the environmental impact associated with its materials and manufacture would score more highly, especially if its use phase impacts are lower.)

- Can our product or service be redesigned so that it mimics nature in a way that is beneficial to its form or function? (Known as biomimicry.)

- Do our products and services maximise the opportunities for environmental education?

- Do we provide information to our customers that explains how to get the maximum environmental benefit / reduce the environmental impact from our product or services throughout its lifecycle? (This is a specific requirement of the draft ISO 14001:2015.)

Upgrading / Reuse / End of life

- Can the product be fully disassembled at the end of its life?

- Is the product modular in nature? (Can parts easily be swapped and / or upgraded? Can the product have multiple functions?)

- Do we / can we provide a take back service for the product at the end of life?

Other

- Have any of the changes made above inadvertently created new environmental impacts that need dealing with (trade-offs)?

- Are there any eco-design quality indicators that you can employ that are specific to your sector such as BREEAM for construction, or an EU Ecolabel? Be aware, however, that external design standards can become tick-box exercises if not used with care.

If you have read this article and want to embed some of the ideas into your organisation, what is the first step and who needs to be involved? – let me know how you get on as I would like to gather some case studies of organisations who are doing this.

By Marek Bidwell (marek@bms-services.com)

Marek Bidwell is director of Bidwell Management Systems, facilitator of a cross-sector group of organisations road-testing the draft 14001: 2015 standard, and author of Making the transition to ISO 14001: 2015: from compliance to opportunity: http://www.bms-services.com/iso-140012015/

Further Reading

- Anderson, 2011: ‘Business lessons from a radical industrialist’, St. Martin’s Griffin

- Benuys, 1997: ‘Biomimicry’, William Morrow

- Bidwell, 2014: ‘Making the transition to ISO 14001:2015 – From Compliance to Opportunity’: http://www.bms-services.com/making-the-transition-to-iso-140012015-paper/

- Braungart and W. McDonough, 2009: ‘Cradle to cradle’, Vintage

- Kane, 2012: ‘Green jujitsu’, DoShorts

- Kane, 2013: ‘Taking Green into the Mainstream’ http://www.terrainfirma.co.uk/blog/2013/01/taking-green-into-the-mainstream.html

- Montgomery, 2003: ‘Happy city’, Penguin Books

- Telenko, C Seepersad, M Webber, 2008: ‘A compilation of design for environment principles and guidelines’, Proceedings of IDET/CIE

- Weizsacker, A Lovins, L Lovins, 1998: ‘Factor four – doubling wealth, halving resource use’, Earthscan

- ISO 14040 series: Life-cycle assessment

- ISO 14062: Environmental management – integrating environmental aspects into product design and development

- BS 8903:2010 (Principles and framework for procuring sustainably)

- Ellen Macarthur Foundation: www.ellenmcarthurfoundation

- WRAP: www.wrap.org.uk

You must be logged in to post a comment.